the black sun

Researches in the history of the occult, the esoteric and theosophical movements, the Volkische and Ariosophical sects and cults, secret societies, magical orders, rune magicians, the cosmic, free energy, techno-occult and avantgarde technology undergrounds and the occult roots of Nazism in Germany, 1900 - 1945

Saturday, September 27, 2014

From Germany to the Distant Stars: Imperial Science Fiction of the Kaiserreich.

Friday, May 10, 2013

1942 - Fairy Research in Nazi Germany

In 1942, Hans Hartmann's Über Krankheit, Tod und Jenseitsvorstellungen in Irland. Erster Teil: Krankheit und Fairyentrückung was published by Max Niemeyer Verlag, as issue 9 of the Schriftenreihe der deutschen Gesellschaft fur keltische Studien.

Its contents: Krankheitsätiologie und Empirie / Orenda der Steine / Orenda der Bäume / Orenda von Haaren und Nägeln / Orenda des Fußwassers / Der böse Blick / Orenda des Priesters und Schmiedes / Orenda des Toten / Krankheit und Tod durch Zauber / Schädigung durch Emanation von Orenda / Schädigung durch Analogiezauber / Zauber mit Körperteilen / Doppelgängerseele und Fairyentrückung / Entrückung der Frauen und Babys bei der Geburt / Entrückung von Kindern / Entrückung durch den Wirbelwind / Entrückung durch Stolpern, Fallenlassen und in di Irre führen / Entrückung im Zustand der Nüchternheit / Entrückung während der Nacht / Entrückung bei Niesen und Schlafen / Entrückung am 1.Mai, in den Pfingsttagen und am Novemberabend / Entrückung bei Tod außerhalb des Hauses / Entrückung und Krankheit / Tote und Fairies / Sargentrückung / Entrückung des "Sterbenden" / und Zurücklassung eines Wechselbalges / Rückkehr aus der anderen Welt / Ethologische Parallelen und religionsgeschichtliche Erkenntnisse für Irland /

A number of sources mentioned in the text: Irish Celtic studies/ Lady Wilde, "Ancient Legends of Ireland"/ E. O'Curry, "Manners and Customs of the Ancient Irish"/ Spiddel, Co. Galway/ Midhros, Co. Cork (P. 164)/ Rathluirc, Co. Cork (P. 115)/ Clonakilty, Co. Cork, P. 87/ Wentz, "Fairy Faith in Celtic Countries", 1911, P. 79/ Bantry, (Beantraighe), Co. Cork, P.77/ Reim, Co. Cork, P. 65/ Crofton Croker, "Fairy Legends and Traditions in the South of Ireland", 1846, P. 62 and 166/ Enniskeane (Inniscein), Co. Cork, P. 167 etc.

Friday, November 16, 2012

The patron saint of steampunk, 1908

More than a century ago, on of the first science fiction series ever appeared in Germany. Entitled Der Luftpirat und sein Lenkbares Luftschiff (The Air Pirate And His Dirigible Airship), it featured a mysterious hero, Captain Mors, the man with the mask whose face and true name nobody knew.

This doomed hero in the vein of Verne's Robur le Conquerant and Captain Nemo had a similarly tragic past. The underworld had killed his wife and children and had framed the brilliant inventor, ensuring that he was hunted everywhere on the globe as a mass murderer and criminal. He had given himself the name 'Mors', since he was already dead in the eyes of public opinion. A man without face and past.

Captain Mors though possesses a giant, metal airship. Equipped with powerful propellers and engines, he has the most advanced weapon in the world. Acting like a Robin Hood, he steals from the rich to give the spoils to the poor, plundering states, corporations and the wealthy but Mors has discovered a higher aim. The unknown wonders of the universe.

Relentlessly Mors toils to finish the construction of a space vessel to further his aim, the flights to Mars, Venus, Jupiter and beyond the borders of the solar system. There he will encounter alien races, extraterrestrial civilizations and ancient mysteries of creation.

The series was forbidden in 1916 by the German military censors, not because of its contents, but because of a shortage of paper. Considered a lowly form of lecture, issues were destroyed, carelessly thrown away or even burned. As a consequence, copies of this series that numbered 165 issues, are very, very scarce.

Worldwide, there is only one almost complete collection. Residing in the Villa Galactica in Germany they are found in the legendary collection of the late Heinz-Jurgen Ehrig. He passed away unexpectedly in 2003. The collection has attained international attention in recent years. He spent 35 years in diligently collecting this unique series. It is the most complete set, only lacking issues 111 and 118. The good news: Villa Galactica has some very interesting pages on the series and it even offers facsimile copies for sale.

Also, make sure to stop by at the Captain Mors, Luftpirat webpage by Jess Nevins for additional information.

Captain Mors is the patron saint of steampunk.

Saturday, July 28, 2007

the German Star Trek, 1925

The history of early German space flight and rocket development is complex, puzzling and riddled with unexpected esoteric influences. Then there is the strong yearning to return to a mythical fatherland, that between the two world wars not always translated itself in earthly geographical coordinates. One fitting example of this is found in a German film that was thought lost forever. Only recently a copy of this film, entitled Wunder Der Schöpfung (The Miracle Of Creation), has been found.

In the film a German scientific team travels through the universe in a spacecraft that serves as the symbol of progress and an age of new technologies, explaining all that is to be seen. Wunder Der Schöpfung was not meant as lighthearted science fiction. Instead, the film that was meant as an educational device begun in 1923. It was released two years later under huge acclaim. In contrast, the same year Hitler's apocalyptic Mein kampf saw print in a first edition of only 500 copies. The book was a difficult seller and not a success. In Wunder Der Schöpfung the end of the world is discussed in optimistic terms, with detailed descriptions of the end of mankind. Four Professors cooperated with the film team, to ensure that everything was based on the scientific knowledge of the day.

Wunder Der Schöpfung was to be, in the words of one critic, UFA's greatest achievment. UFA put itself more and more in the mindframe necessary for its most ambitious project yet: Fritz Lang's Metropolis, that was relased in 1927, two years after Wunder Der Schöpfung. Contrary to Metropolis that obtained only a lukewarm reception, Wunder Der Schöpfung was a tremendous hit. It still is a remarkable film with for that time highly ingenious and elaborate special effects.

There is also a general feeling amongst connoisseurs that certain scenes might have served as a template for Stanley Kubrick's 2001.

More stills can be found here, and the trailer here.

There is also a general feeling amongst connoisseurs that certain scenes might have served as a template for Stanley Kubrick's 2001.

More stills can be found here, and the trailer here.

At the dark heart of Lemuria, 1917

In 1917, a book with strange and uncanny tales that bore the remarkable title Lemuria was published in Germany. The horrible blackness and the almost pathological nature of its haunting illustrations closely connected to the spirit of the German nation, as the fatherland was desperately struggling to survive the onslaught that was the First World War. Lemuria struck a chord in the German psyche and was reprinted well till after the Great War that should have ended all wars, but didn't.

The name Lemuria was introduced in the 19th century by geologists speculating on a lost continent in the Indian ocean. The term was quickly seized upon by occultists and theosophists in the wake of Blavatsky's unveilings. Blavatsky saw the Lemurians as reptilian in nature, being the Third Root Race, having followed the Hyboreans, The Second Root Race. However, the Lemurians used black magic and corrupted themselves by intermingling with other species, necessitating the gods of destroying Lemuria after which they created the Fourth Root Race, that of Atlantis. One notes the origin of much current speculation on the reptilians, but also the influence on Ariosophy. The nucleus of Blavatsky's theories on Lemuria are similar to those of Lanz von Liebenfels, founder of the Ordo Novi Templi, an order modelled partially on The Knights Templar. Liebenfels also edited the antisemitic periodical Ostara of which it is claimed that an impressionable Adolf Hitler read these during his years in Vienna.

In Lemuria we encounter one short story, entitled Der Bogomilenstein (The Stone of the Bogomil), that may betray some of Strobl's cultural predilections. The Bogomils were spiritual forerunners of the Cathars and, some say, the Knights Templar. German author Hanns Heinz Ewers wo would later write the National-Socialist anthem the Horst Wessel Lied published Lemuria in a series titled Gallerie der Phantasten (Gallery of the Fantasts) with publisher Georg Muller Verlag in Munich. The author of Lemuria was Austrian writer Karl Hanns Strobl (1877 - 1946), who during his life also was the editor of Der Orchideengarten, about which I posted earlier on this blog.

Strobl wrote many unusually dark, strange and gruesome fantastic tales, collected in, amongst others, Lemuria and, For instance, his book Od that was released in 1930. 'An adventure-romance of Baron von Reichenbach. A Zeileis-fate 50 years ago. The discovery of the magical man', it's blurb read.

During the First World War , Strobl was a messenger, a position not unlike that of his fellow Austrian Adolf Hitler. After the war, Strobl developed a strong sympathy for the Nationalsocialist cause. In 1938 Strobl worked in an important position in the Ostgau, leading a department of Goebbel's Reichsschrifttumskammer. This lead to his arrest by the Soviet troops in 1945. Strobl was forced to work at road construction for a while. He was released due to age and very poor health.

Impoverished, Strobl died a year later in a home for the elderly near Vienna. At the time of his death, the Allied forces had prohibited his works to be published. Once his more than hundred published book titles commanded multiple reprints and huge successes. Strobl formed, with Gustav Meyrink and Hanns Heinz Ewers the three dark princes of the German horror and supernatural.

The name Lemuria was introduced in the 19th century by geologists speculating on a lost continent in the Indian ocean. The term was quickly seized upon by occultists and theosophists in the wake of Blavatsky's unveilings. Blavatsky saw the Lemurians as reptilian in nature, being the Third Root Race, having followed the Hyboreans, The Second Root Race. However, the Lemurians used black magic and corrupted themselves by intermingling with other species, necessitating the gods of destroying Lemuria after which they created the Fourth Root Race, that of Atlantis. One notes the origin of much current speculation on the reptilians, but also the influence on Ariosophy. The nucleus of Blavatsky's theories on Lemuria are similar to those of Lanz von Liebenfels, founder of the Ordo Novi Templi, an order modelled partially on The Knights Templar. Liebenfels also edited the antisemitic periodical Ostara of which it is claimed that an impressionable Adolf Hitler read these during his years in Vienna.

In Lemuria we encounter one short story, entitled Der Bogomilenstein (The Stone of the Bogomil), that may betray some of Strobl's cultural predilections. The Bogomils were spiritual forerunners of the Cathars and, some say, the Knights Templar. German author Hanns Heinz Ewers wo would later write the National-Socialist anthem the Horst Wessel Lied published Lemuria in a series titled Gallerie der Phantasten (Gallery of the Fantasts) with publisher Georg Muller Verlag in Munich. The author of Lemuria was Austrian writer Karl Hanns Strobl (1877 - 1946), who during his life also was the editor of Der Orchideengarten, about which I posted earlier on this blog.

Strobl wrote many unusually dark, strange and gruesome fantastic tales, collected in, amongst others, Lemuria and, For instance, his book Od that was released in 1930. 'An adventure-romance of Baron von Reichenbach. A Zeileis-fate 50 years ago. The discovery of the magical man', it's blurb read.

During the First World War , Strobl was a messenger, a position not unlike that of his fellow Austrian Adolf Hitler. After the war, Strobl developed a strong sympathy for the Nationalsocialist cause. In 1938 Strobl worked in an important position in the Ostgau, leading a department of Goebbel's Reichsschrifttumskammer. This lead to his arrest by the Soviet troops in 1945. Strobl was forced to work at road construction for a while. He was released due to age and very poor health.

Impoverished, Strobl died a year later in a home for the elderly near Vienna. At the time of his death, the Allied forces had prohibited his works to be published. Once his more than hundred published book titles commanded multiple reprints and huge successes. Strobl formed, with Gustav Meyrink and Hanns Heinz Ewers the three dark princes of the German horror and supernatural.

Saturday, September 09, 2006

Aryan Gods from Hyperborea

Otto Sigfrid Reuter has obtained in recent years the dubious sobriquet of, together with Hermann Wirth, the founding father of Nazi Archaelogy. Reuter (1876 - 1945) was a staunch Ariosophist and founder of several Aryan-Christian orders such as the Deutschglaubige Gemeinschaft and the Germanische Glaubensgemeinschaft, founded in 1911 and 1912 respectively. The aim of these orders was the fusion of blood and religion, hence, membership was restricted to "true Aryans". Some have it that these orders still exist today.

Reuter's reputation rests predominantly on his book Germanische Himmelskunde (German Sky Lore), published in 1934. The idea behind his orders was to rid Christianity of the Jewish influences to make it more digestible for Germans. Reuter's book Sigfrid oder Christus? Ein Kampfruf (Sigfrid or Christ? A Battle Cry), published in 1908, reflects his philosophy. Highly succesful, it was reprinted in 1910.

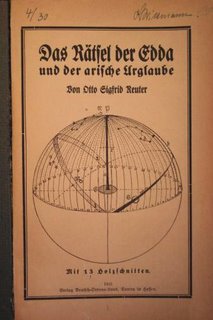

His next book, Das Ratsel der Edda und der Arische Urglaube (The Riddle of the Edda and the Ancient Religion of the Aryans), published in 1921, 1922 and 1923, was a continuation of his ideas. Reuter believed in the reality of the Edda 'like a maniac' as one authority has it. This was one of the reasons why Reuter left various nationalist and racist German orders which stood at the cradle of National Socialism. It appears that Reuter could not tolerate ideas that were not of his own.

|

| Otto Sigfrid Reuter on his 60th birthday as published in Mannus, issue 28, 1936, found here. |

Reuter's philosophy was based on the study of the Edda was that the oldest human culture had come from a Germanic North. The idea of a world axis - the Axis Mundi or Irminsul, the column that supports heaven -was invented by the Germans and the names of all the constellations were based on ancient German science that had its origin aeons before our time. He also believed that the divine was to be found within the German race. Reuter died on 5 April 1945 by heart attack. Allied bombs had wrecked his home earlier. With him perished his dreams of a prehistoric Aryan supercivilisation that had encoded its secret wisdom in the stars, in the Gotterdammerung of the Third Reich.

|

| Das Ratsel der Edda und der Arische Urglaube, 1922, page 48. |

But all

this does not do Reuter’s book justice. Reading the antiquated Fraktur Schrift

is like visiting another world, far removed from the shallow modernity of our times. I

wonder how many of us have read the book; I found no recent scholarly assessment or critical treaty of its

contents. Reuter’s book is full of strange ideas and should be placed in the larger context of ultra-conservative illuminated literature. Reuter’s interpretations of

the ‘Nordic Rock paintings’ (see pages 47-48) can be considered as a forerunner

of the school of ancient astronauts. Reuter writes:

“Opposed to that, examining the rock drawings… we must notice:

1. .. a general bird headedness, that seems to point to their flying nature;

2. their floating composure;

3. their mostly uplifted hands, often extra sized;

4. the connection of these figures with circles, many sliding coils, ships and chariots;

5. the interspersion of the images with numerous single and grouped points, which are replaced in some images with radiant stars;

6. the connection of the figures and companions with these single or grouped together standing points or stars;

7. the absence of house images and earthly needs.

Reuter concludes by writing that ‘it

is not about earthly, but heavenly paintings and representations of gods.’

Radiant stars, godly beings and heavenly chariots as sacred Germanic lore.

Reuter on page 49:

“ The images of the ships. We know from ancient times that the sun and the moon were accosted as ships of the heavens, which sail away on the sea of heaven. The depiction of such ships is not only known to the southern and eastern peoples, but also to the Germans (as Tacitus reports). Even in the Edda one finds an elaborate entry on this…”

|

| Reuter's 'Germanic Worldview' as depicted in his Das Ratsel der Edda und der Arische Urglaube, 1922, page 87.

I acquired an original edition of

Reuter’s book years ago, but its extremely brittle paper and worn out

leather binding gave me concerns in regards to preserving this unique artefact

of a bygone era. Fortunately since then a digital scan of the book can be downloaded here. More biographical data provided by his daughter Irmgard Teubert, written in 1985, are found here and the text of a letter by SS-Oberscharfuhrer Lasch, asking Reuter for help in selecting a proper teacher of Germanic 'Himmelskunde' for Wewelsburg, dated 14 October 1935 is found here. Reuter's essay 'Der Himmel uber den Germanen' is found, translated and annotated, here.

|

Crossing the Abyss, 1931

Thus, when the might of the German war machine unleashed its Blitzkrieg (thunder war) on an ill prepared Europe - its new strategic formula and technological terror tactics were reminiscent of that early subgenre in science fiction entitled the Future War Tale. While the sirens of the Stuka dive bombers, howling like the legendary Walkuren or Banshees, transformed whole cities into hellish cauldrons of the alchemical Prima Materia, other minds in Germany kept on dreaming of soaring space ships and the conquest of space.

Jetzt gehort und Deutschland, morgen das ganse Sonnensystem (now Germany belongs to us, tomorrow the whole solar system), as The Illuminatus Trilogy coyly states, is the apt slogan. One could perhaps remark that, since Germany had lost most of its colonies, space formed the final formidable frontier.

|

| Another edition with its variant title (airship in space) published in 1939 |

Heichen, who lived in Berlin, already had published propaganda lecture to kindle pattriotic interest during the outbreak of the First World War. During the Third Reich his pattriotism adhered to the National Socialist cause. In Heichen's book, the protagonists travel to the planet of Sigma, where they encounter highly developed humanoids. Heichen died in Berlin in 1970, having witnessed the landing of the first man on the Moon the year before, made possible by his fellow countryman Wernher von Braun, who had led the rocket development program of the Third Reich before and during World War II.

Saturday, September 02, 2006

The German Mission to Mars, 1910

Then there was Albert Daiber who published his Die Weltensegler, drei jahre auf dem Mars (The World Sailers, three years on Mars) in 1910 and its sequel Vom Mars zur Erde (From Mars to the Earth) in 1914. Albert Ludwig Daiber (1857 - 1928) was born in Germany but died in Chile. Apparently the reactions to his succesful book Elf Jahre Freimaurer (Eleven Years Freemason) that was published in 1905 were such that he decided to emigrate to Chile.

In Daibers' books we encounter Martians called 'Marsites' who live in a scientific utopia. And where certain rumours have it that in 1944 or 1945, towards the end of World War 2 a secret German SS mission to Mars was actually undertaken in a 74 meter diameter Haunebu 3 flight disc, in Daiber's book the journey to Mars is started in 1942. The names of the seven world sailors, German scholars and professors, all begin with the same Letters. Thus we have a Paracelcus Piller, A Bombastus Brumhuber and so forth. The main protagonist, the leader of the expedition and its spiritual father is named Siegried Stiller or SS.

Noordung's solar space station, 1928

A beautiful museum was erected in Slovenia to preserve and honor the work of early space pioneer Herman Potočnik (pseudonym: Noordung).

In 1925, a chronically ill and impoverished engineer in Vienna devoted himself entirely to space travel. His name was Herman Potočnik (1892 - 1929), and in 1928 his only book, Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums - der Raketen-motor (The Problem of Space Travel, the Rocket Motor) was published.

In it, he gave detailed plans for the construction of a geostationary space station, solar powered and manned, called Wohnrad (Habitat Wheel). The design consisted of a ring with an outer diameter of 164 feet (50 metres) for living quarters, two large, concave mirrors for solar energy assembled to one end of the central axis, and an astronomical observation deck. His was among the first to propose a wheel-shaped space station in order to to create artificial gravity. The book did not bring Potočnik fame or fortune, however. Engineers in Vienna dismissed his ideas as sheer fantasy, although it was of influence on the German Verein für Raumschiffahrt (The Space Flight Society) that was located in Berlin. Founded in 1927, it counted amongst its members Hermann Oberth and Wernher von Braun.

The Verein für Raumschiffahrt also published a magazine titled Die Rakete (The Rocket), from 1927 till 1929, sporting some evocative covers as seen below.

Potočnik too was a member of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt. He died in Vienna on August 27, 1929 of pneumonia, in great poverty. Parts of his magnum opus were translated and in English, in the July, August and September issues of Gernsback's Science Wonder Stories in 1929. Oberth coined the phrase 'space station'to describe Potočnik's concept. Let us here, make place for Hermann Noordung as he wished himself to be known, and give the last words to him:

"Conquering space! It would be the most grandiose of all achievements ever dreamed of, a fulfillment of the highest purpose: to save the intellectual accomplishments of mankind for eternity before the final plunge into oblivion. Only when we succeed in transplanting our civilization to other celestial bodies, thus spreading it over the entire universe, only when mankind with all its efforts and work and hopes and with what it has achieved in many thousands of years of striving, only when all of this is no longer just a whim of cosmic events, a result of random incidents in eternal nature's game that arise and die down with our little Earth so large for us and yet so tiny in the universe will we be justified to feel as if we were sent by God as an agent for a higher purpose, although the means to fulfill this purpose were created by man himself through his own actions."

Wednesday, August 23, 2006

The Garden of Orchids

|

| The first issue of Weird Tales, March, 1923. |

First published in 1919 under the editorship of Karl Hans Strobl (1877 - 1946), an Austrian writer of dark and unusual horror tales who also was the publisher together with Alfons von Czibulka, it ran until 1921. Der Orchideengarten was more than a magazine devoted to the fantastic; appropriately founded in the year that across the ocean, Charles Fort would publish his Book of the Damned, the magazine too, devoted space to anomalous phenomena: "...we no longer dismiss as nonsense all things that are not explicable in terms of the known laws of physics. Mysterious connections between human beings, independent of spatial and temporal separation, spooks, the appearance of ghosts, all are again in the realm of the possible..." as the editorial in the second issue of Der Orchideengarten explained.

Der Orchideengarten featured some truly lurid and haunting covers, and since I originally wrote this post, has achieved recognition as 'the world's first fantasy magazine'. Many of its striking covers can be admired online such as the following ones, beautifully scanned by Will Schofield.

Some of the absolutely striking interior illustrations of Der Orchideengarten can be found here, also owing to the good grace of Will Schofield who has curated an incredible selection from his private collection. Seeing these images, one can only wonder what it would have been like, had Der Orchideengarten also published the tales of Clark Ashton Smith and Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Some of the interior illustrations in Der Orchideengarten certainly merit such a thought. Lee Brown Coye would have felt at home.

|

| Hugin, October 1919, featuring a swastika in an advert for an electrotechnical company in Sweden. |

|

| Covers and interior illustrations of Gernsback's magazines were predominantly done by Frank R. Paul (1884 - 1963). |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)