|

| The first issue of Weird Tales, March, 1923. |

It is often claimed that the first magazines devoted to science fiction and the fantastic orginated in the United states and exerted their influence on the emerging fields of ufology, the paranormal and the fortean. The venerable

Weird Tales was launched in March 1923 and is often held as the first magazine published devoted to the weird. But Austrian magazine

Der Orchideengarten (The Garden of Orchids) preceded the American venture with four years.

First published in 1919 under the editorship of

Karl Hans Strobl (1877 - 1946), an Austrian writer of dark and unusual horror tales who also was the publisher together with

Alfons von Czibulka, it ran until 1921.

Der Orchideengarten was more than a magazine devoted to the fantastic; appropriately founded in the year that across the ocean, Charles Fort would publish his

Book of the Damned, the magazine too, devoted space to anomalous phenomena: "...we no longer dismiss as nonsense all things that are not explicable in terms of the known laws of physics. Mysterious connections between human beings, independent of spatial and temporal separation, spooks, the appearance of ghosts, all are again in the realm of the possible..." as the editorial in the second issue of

Der Orchideengarten explained.

Der Orchideengarten featured some truly lurid and haunting covers, and since I originally wrote this post, has achieved recognition as

'the world's first fantasy magazine'. Many of its striking covers can be admired online such as the following ones, beautifully scanned by Will Schofield.

Some of the absolutely striking interior illustrations of

Der Orchideengarten can be found

here, also owing to the good grace of Will Schofield who has curated an incredible selection from his private collection. Seeing these images, one can only wonder what it would have been like, had

Der Orchideengarten also published the tales of Clark Ashton Smith and Howard Phillips Lovecraft. Some of the interior illustrations in

Der Orchideengarten certainly merit such a thought.

Lee Brown Coye would have felt at home.

Strobl published his gruesome, unusual and haunting tales in a number of books with titles like

Lemuria (1917) and

Gespenster im Sumpf (1920) (Spooks on the Moor). Swedish science fiction magazine

Hugin (1916 - 1920) preceded

Der Orchideengarten with three years and Gernsback's magazines like

Wonder Stories, Air Wonder Stories, Science Wonder Stories (first issued 1929) and

Amazing Stories (started in 1926) with even a decade. Hugin's cover art though definitely lacked the dark fantastic and visionary strain so apparent in

Der Orchideengarten.

|

| Hugin, October 1919, featuring a swastika in an advert for an electrotechnical company in Sweden. |

The editor of

Hugin, Otto Witt (1875 - 1923) studied at the technical university of the German town of Bingen, at the same time that Hugo Gernsback studied there. Gernsback, born in 1884 as Gernsbacher, at ten years of age was an insatiable reader. At that time he found a translation of

Percival Lowell's Mars as the Abode of Life. He devoured the book and went into a delirious phase that lasted two days, during which he rambled almost non-stop about the Martians and their technology, a theme to which

he would return in later years. This experience would prove a pivotal point in the life of young Gernsbacher.

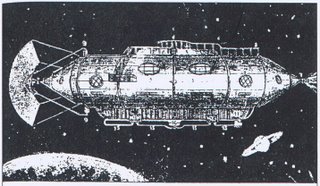

|

| Covers and interior illustrations of Gernsback's magazines were predominantly done by Frank R. Paul (1884 - 1963). |

In 1904, then still named Gernsbacher, he went to the United States and changed his name into Gernsback. There he would come to know inventors like Tesla, de Forrest, Fessenden and Grindell-Matthews. Gernsback would also publish an impressive list of science fiction magazines and coin the very phrase 'science fiction'. As such, a case is to be made for Germany as the birthplace of 20th century weird and science fiction magazine publishing.

+by+Werner+Graul.jpg)